Go for Rubyists. Part 8. Concurrency in Go, Ruby and Elixir

Hey folks, hope you had a great weekend and it’s time to learn something new! Today we will observe the concurrency topic, and since it’s not such a fair comparison for Ruby, who’s forte is definitely not concurrency, I will add Elixir to today’s article. However, still, since the series is about Go, the main focus will be on it. Don’t expect a performance comparison, I believe it’s not fair to compare these languages since they all have slightly different focuses.

Let’s first set some baselines. Few terms we operate, when speaking about concurrency are:

- Thread

- Process

- Concurrency

Thread

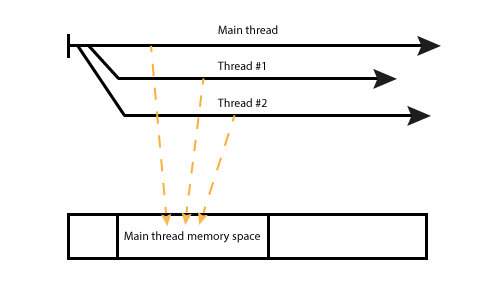

Thread is a sequence of computer instructions, which can be executed independently and usually managed by the OS. It is important to understand that multiple threads can belong to the same process and share its memory. They’re executed not exactly in parallel, but sequentially with interruptions.

Process

Process is a bigger thing. It has its own memory address space, can be executed in a real parallel way by leveraging multiprocessor architecture and the communication between them is usually possible only by using the OS-defined mechanisms.

Concurrency

In general, concurrency means the ability of functions to be executed “in parallel”. The traditional way of achieving concurrency is by using multiple threads.

Ruby MRI

If you’re working with Ruby, you most likely know that not such a long time ago Ruby didn’t have “real” threads at all. The only threads we had were “green threads”. Which are still executed in the same thread, so they are not really threads, but it’s too early to blame Ruby! We now have native threads, but using GIL, which stands for Global Interpreter Lock. It is a perfect solution, when you want to use only one processor core. Because even if you have more, GIL is still one and it doesn’t really leverage the multi-processor advantages. Also, speaking about the future of Ruby, the community and Matz himself started moving towards having less safe, but more viable concurrency models and apparently we will see the Actor model in Ruby.

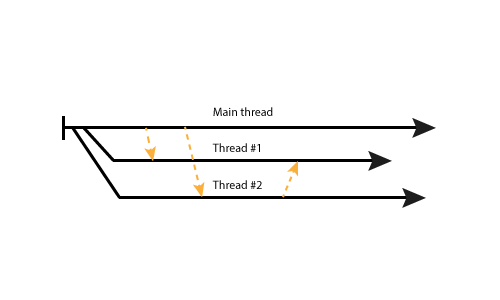

Ruby inter-thread communication

Sometimes you want your threads to exchange some data, e.g. if your thread intended to run some other threads, which can then be waiting for some data be computed somewhere else and react only then. Ruby has a built-in solution for this, which is the Queue class. It is shared among all threads you spawn and thread can take an object from the queue and remove it from there. I know, it’s not ideal, since you cannot “send” object to a specific thread really, only by manual filtering or having multiple queues per process, which is not so bad actually. However as we will see further, there are more useful interaction models.

Fibers

Fibers are even more light-weight concurrency abstraction than threads. The main difference is that they are managed only by a developer. So you can manually start, stop and resume them, without the VM.

Further reading

I didn’t cover the whole topic, so if you’re interested in reading more about concurrency in Ruby, try these articles:

- https://engineering.universe.com/introduction-to-concurrency-models-with-ruby-part-i-550d0dbb970

- https://medium.com/@WesleyDavis/multi-threading-in-ruby-1c075f4c7410

- https://medium.com/@franzejr/ruby-3-mri-and-gil-a302577c6634

- https://ruby-doc.org/core-2.4.1/Fiber.html

Example

An example of how the simplest Ruby app with threads may look like:

def print_numbers(thread_number)

(0..5).each do |j|

p "Thread: #{thread_number}, number: #{j}"

sleep(Random.rand)

end

end

(0..5).each do |i|

Thread.new { print_numbers(i) }

endIt will print something similar to:

"Thread: 5, number: 1"

"Thread: 0, number: 1"

"Thread: 5, number: 2"

"Thread: 2, number: 1"

"Thread: 5, number: 3"

"Thread: 0, number: 2"

"Thread: 4, number: 1"

"Thread: 1, number: 1"

"Thread: 3, number: 1"

"Thread: 4, number: 2"

...etcElixir

Elixir is a programming language, built on the Erlang VM and heavily influenced by Ruby. So it has all the concurrency advantages of Erlang, but Ruby-like expressive syntax.

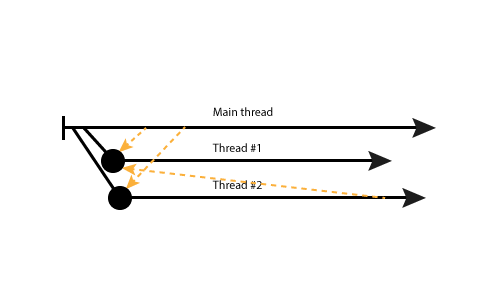

Concurrency model

Elixir incorporates a totally different concurrency model, which says “share nothing”. So no shared memory, no shared queue to take data from. Its model name is “Actor model”. Basically, it means that every process operates on its own and can interact with any other process with the known id by sending a message to it.

As for the developer, it means that no GIL exists, and inter-process communication is easily possible. Just one thing to notice, the processes I’m talking about here are not OS processes which you think about, but OTP processes, which is a way lighter alternative.

Further reading

- Elixir multiple processes basics

- Agents and tasks in Elixir

- Introduction to OTP GenServers and Supervisors

And other articles of my friend Vitaly :)

Example

defmodule NumberPrinter do

def print_numbers(thread_number) do

Enum.each 1..5, fn(j) ->

IO.puts "Thread: #{thread_number}, number: #{j}"

:timer.sleep(Enum.random(0..500))

end

end

end

Enum.each 1..5, fn(thread_number) ->

spawn(NumberPrinter, :print_numbers, [thread_number])

end

I believe it’s not the most idiomatic way of writing such a function in Elixir, but it’s not my everyday language, so I have an excuse :)

Go

Golang uses a mechanism, called goroutines. The name is inspired by the term coroutine and which is pretty much what I’ve explained in the Fibers section of Ruby block. Though it doesn’t mean that Go’s goroutines have much in common with Ruby’s threads or fibers.

Goroutines and Threads

The main confusion I had was to think of goroutines as of threads. Yet they are actually pretty different. Here are some of the differences:

- Thread usually allocates about 1MB of RAM. Goroutine takes just 2KB at the start. Just to mention, Elixir’s threads allocate even less, about 0.5KB.

- Since their size is smaller, you can run much more of them and their spawn time is faster.

- Threads belong to one process and hence one processor. Goroutines can also use multiple processors/cores.

Example

Since we’re learning Go here, I will provide an example right ahead.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func print_numbers(thread_number int) {

for j := 0; j < 5; j++ {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("Thread: ", thread_number, ", number: ", j)

}

}

func main() {

for thread_number := 1; thread_number < 6; thread_number++ {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

go print_numbers(thread_number)

}

print_numbers(0)

}

The conversion respects the original HTML structure, turning tags into their Markdown equivalents, and maintaining the content, including code snippets and links. Adjustments might be needed depending on the Markdown parser’s specifics, especially concerning the handling of inline HTML or templating syntax.

In Golang, in order to spawn a goroutine, the only thing you have to do is to call a function using the go command. In the example above, I show that you can call the print_numbers function both asynchronously as a goroutine and in the main thread.

Inter-goroutine communication

The communication model in Go lies somewhere in between a shared queue and messages. Golang uses so-called “channels” to pass messages/objects from one goroutine to another. The main difference with a shared queue is that a channel is not shared among all goroutines, but you can manually decide, to which goroutines to provide access to it. The main difference with messages of OTP’s Actor model is that in Elixir, you pass messages by the PID, but in Go, anyone having a channel reference can read from it.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func print_numbers(thread_number int, messages chan string) {

for j := 0; j < 5; j++ {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

messages <- fmt.Sprintf("Thread: %v, number: %v", thread_number, j)

}

}

func main() {

messages := make(chan string)

for thread_number := 1; thread_number < 6; thread_number++ {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

go print_numbers(thread_number, messages)

}

for {

message := <-messages

fmt.Println(message)

}

}

In this example, instead of printing strings right in the goroutine, we push them to the channel and then in the main function, we’re constantly reading from the channel and printing everything stored there.

If you’re still not quite sure what the difference is between these three implementations, below you’ll find a list of useful articles to delve deeper.

Further reading

- Goroutines vs Threads

- Why goroutines are not lightweight threads

- Comparing Elixir & Go

- Ruby vs Elixir vs Go: A concurrency comparison

In the next post, we will discover goroutines deeper, addressing such topics as buffered channels, direction selection, and pipelines.

I hope it was useful, feel free to add suggestions, share, or even appreciate by clicking on a big orange button below %)